July 22, 1975, was a

busy day for Boston Herald photographer Stanley Forman. Early in

the day he climbed towers and rode elevators all over Boston to get

pictures of the city's skyline for a Sunday magazine feature. During

that time, he remained on call for other daily assignments.

July 22, 1975, was a

busy day for Boston Herald photographer Stanley Forman. Early in

the day he climbed towers and rode elevators all over Boston to get

pictures of the city's skyline for a Sunday magazine feature. During

that time, he remained on call for other daily assignments.

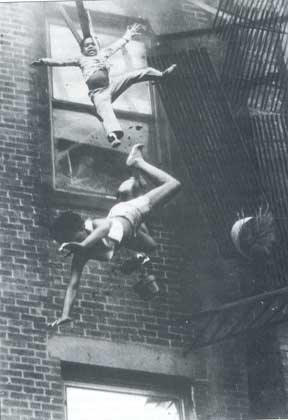

After returning his film to the newspaper, he was hoping to leave for the day when a call came about a fire in one of the city's older sections of Victorian row houses. The dispatcher mentioned that some people might be trapped in the burning structure. Forman followed the fire engine to the scene and heard on his scanner an SOS ordering a ladder truck to the scene. When he arrived, he followed a hunch and ran down the alley to the back of the row of houses.

There he saw firefighter Bob O'Neil and two people, a two-year-old girl and her nineteen-year-old godmother, on the fifth-floor fire escape. The fireman was calling for help from a fire truck below. The truck raised its aerial ladder to the trio. Forman climbed aboard the bed of the truck to get a better angle on what he anticipated would be a routine rescue.

Meanwhile the WBZ radio traffic helicopter had landed on the next roof, and the pilot was offering to take the child. Though he is visible in most of the photos, he never got a chance to help.

As Fireman O'Neil reached for the ladder of the fire truck below, there was a loud noise-either the sound of a scream or the shriek of metal bending. The fire escape gave way, sending the two victims falling and leaving O'Neil clinging for his life to the ladder. Forman saw it all through his 135 mm lens and took four photos as the two were falling, before turning away to avoid seeing them hit the ground. The woman, Diana Bryant, broke the fall of the girl, Tiare Jones, who survived. Bryant sustained multiple head and body injuries and died hours later.

O'Neil was shaken by the experience. "Just two more seconds. I would have had them," he said repeatedly. Though Forman took a few more pictures, he was shaking too much to hold the camera still.

Returning to the newspaper, he waited anxiously to see if he had the photos that he thought he had. When it was obvious he did, he stayed to help with some of the prints and went home, exhausted. At 8:00 P.M. he learned that Bryant had died. He wondered if the newspaper would still run the photos.

He saw the first morning edition of the paper shortly after 2:00 A.M. and was surprised to see that the key photo in the sequence (the one reprinted here) was printed on page one and measured 1l){2 inches by 16){2 inches-virtually the entire tabloid page. A full sequence of the four photos ran on page three.

By 4:00 A.M., Forman had made a set of prints for the Associated Press, which gave the pictures worldwide distribution that same day. Tearsheets on the photos came from 128 U.S. papers and several foreign countries.

Within twenty-four hours, action was taken in Boston to improve the inspection and maintenance of all existing fire escapes in the city. Fire-safety groups around the country used the photos to promote similar efforts in other cities.

Numerous awards came as well. The Pulitzer prize committee gave Forman its 1976 news photo prize. The National Press Photographers Association named the photo Picture of the Year. Several other groups, including the Society of Professional Journalists, honored the photo as well. Forman went on to win the Pulitzer prize again the following year, making him the only photographer to win consecutive Pulitzer prizes for news photography. His awards earned him a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard and lecture engagements around the world.

From Media Ethics: Issues and Cases, 4th edition. Philip Patterson and Lee Wilkins. McGraw-Hill, 2002. Case IV-C.

In

early spring a family in Florida went to a local park to picnic and

relax. Their 9-year-old son, ignoring clearly posted “No Swimming” signs

went into the lake and drowned. A local daily newspaper photographer, in

the park for general springtime pictures, saw the family and took this

picture. The dead body of the 9-year old is in the open body bag in the

lower left corner. The photo ran on the front page of the local daily,

and was picked up by Associated Press and run in many papers nationwide.

In

early spring a family in Florida went to a local park to picnic and

relax. Their 9-year-old son, ignoring clearly posted “No Swimming” signs

went into the lake and drowned. A local daily newspaper photographer, in

the park for general springtime pictures, saw the family and took this

picture. The dead body of the 9-year old is in the open body bag in the

lower left corner. The photo ran on the front page of the local daily,

and was picked up by Associated Press and run in many papers nationwide.

The photo was taken on public property, so there is little question of legality. But what about the sensitivity of the family?

There is little debate about the newsworthiness of the story for the local daily: a child drowned in a public park in full view of hundreds of people. But do you need the photo to tell the story?

There is also little disagreement about the power of the photo. It is, from some perspectives, a great shot: it communicates the tragedy of the accident and the pain of the family extremely effectively.

One argument for running the picture is that it will act as a deterrent for other families who, presumably, will watch their kids much closer because of the shock value of the picture. This has merit, because the dead child and the grieving family will communicate the safety message far more powerfully than just a headline and story. This is the traditional drunk driving accident picture argument, with gruesome pictures of drunk driving accidents shown for shock value. This policy almost certainly raised awareness of drinking and driving.

However, there is always the sensational factor. This is a sensational photo, and will sell papers. How much should that factor in?

It also has prize-winning potential. There is benefit to the photographer and to the newspaper to win awards. But you can’t enter contests with pictures you didn’t publish.

How much should the sensitivity of the family weigh in the decision to run this photo or not?

Revictimization

The term which was eventually coined to apply to this type of question is “revictimization”: running the photo adds to the pain of the grieving family and friends. How valid is this as a news judgment? How should it weigh against other concerns? How important is the traditional public right to know and when does it take a back set to private grief.

Department of Communication, Seton Hall University