|

9/16 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

Socrates' Apology

Socrates

(469-399 B.C.E.) was Plato's teacher. In the course of

great civil unrest in the years following Athens' defeat in the

Peloponnesian War, he was brought to trial on charges of

introducing foreign gods and of leading the youth of Athens

astray. The Apology was apparently composed not long after

Socrates' death; it presents itself as Socrates' defense against

the charges levied against him, and his speech to the jury after

he was found guilty. He was sentenced by the jury to

execution. The text indicates that Plato was present at

the trial; other dialogues suggest that Plato himself was also

present at Socrates' death. The issues of truth and

justice that the death of Socrates posed remained central issues

in Plato's thought. |

The Temple of

Apollo at Delphi; the Oracle was inside the temple. |

Do you think Socrates was

"wise"? Why? What might "wisdom" be? What passages in

his speech strike you as particularly noteworthy? What's there

that surprises you? Why? Socrates says (38a) that "the

unexamined life is not worth living for men." Do you agree with

him? Why or why not? What if he is right? What do you

think of his reaction to his impending death? Why? What do

you make of Socrates' final comment? How does Socrates know what he

knows? Can you know that way? Should you? What should

you do? How can you get to the transcendently true? How do

you know? What can we learn from Socrates' search for truth?

Before you come to class,

write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal in Blackboard with your

first reflections on today's reading.

There are three main goals of the journal

assignment.

-

To provide opportunity for reflection

and integration of the course material at a personal level.

-

To provide a place to practice and

improve your writing skills.

-

To have regular contact with the

professor regarding your thoughts and ideas about what you are

learning.

It is up to you to decide on what you want

to write about for each entry. However, you must choose to discuss

something related to the course. This means you can reflect on what you

are learning from reading the assigned text, or from class discussion,

or from your discussing the text with your classmates. Whatever you

choose, we should be able to tell that you are taking the course when we

read your journal entry. So, please don't tell us what you ate for

breakfast, or who you hung out with on the weekend. Also, work hard to

avoid simply summarizing the reading. You can do that in your reading

notes. The point of the journal is to think about the material and to

let us know what you're thinking. What are you learning? What questions

occur to you, and what insights have you gained through engagement with

the course material? This is also the place that you can consider the

implications of what you are reading/learning, and ways that these texts

might intersect with your own life and community

We expect you to write as cogently as possible in your

journals. We also expect to see improvement in your critical thinking

and writing skills over the course of the semester reflected in your

journals. We will provide regular feedback including suggestions on ways

to improve. Please read this feedback and use it to strengthen your

work.

You should write your journal entries in Word and then cut

and paste them onto the Blackboard site. Do this by clicking on the

button marked Journal that is listed on the left of the Blackboard site

for our course. After clicking on Journal, click on new entry and paste

your work into the window.

Read

before class:

-

Plato's

Apology, Crito (The Last Days of Socrates)

Recommended additional reading:

|

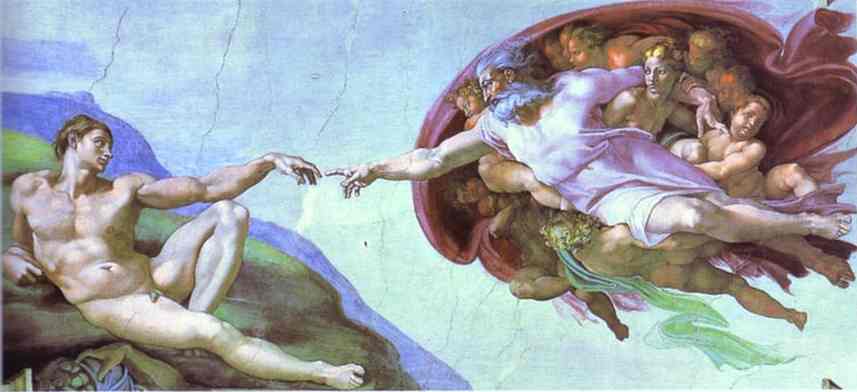

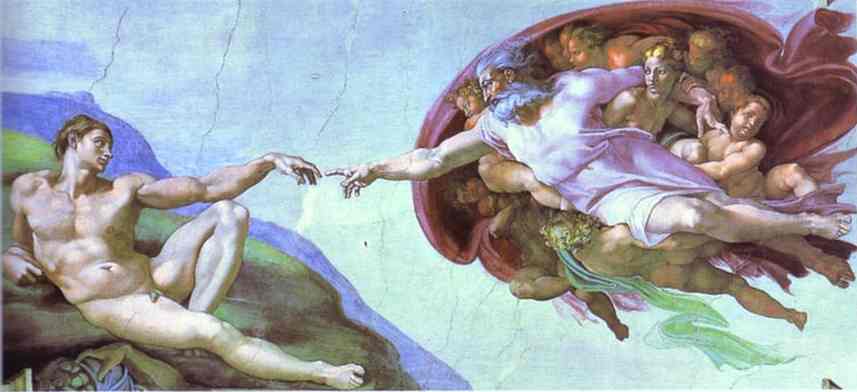

Foundation Stories

Who are we

and where do we come from? The community and the individual.

What do these stories tell us about the self-understandings of the

people who told these stories, and of those who collected them?

What do they say one should do? What do they say it means to be

human? How should society be organized? Why?

|

Read before class:

|

9/30

Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

The Buddha and Buddhist teachings

Siddhartha

Gautama (traditionally 566 - 486 B.C.E., although some modern

scholars date him about a century later) is known to us as the

Buddha, the Awake One. At his enlightenment at the age of

35, he came to understand what he taught as the Four Noble

Truths: that all life is suffering, that the cause of suffering

is desire, that suffering can be ended, and that the way to end

suffering is the Noble Eightfold Path: right understanding,

right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood,

right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation.

This "Middle Way", between bodily indulgence and harsh physical

asceticism, focuses on the concentration of the mind to a proper

understanding of reality. He spent the rest of his life

teaching this

dharma (truth, teaching, thing); his teachings were

collected orally after his death, and much later reduced to

writing. During his lifetime, he gathered thousands of

followers, who adopted his mendicant style of living; these

monks were his first

sangha, or community.

|

Buddha,

Kamakura, 13th century

|

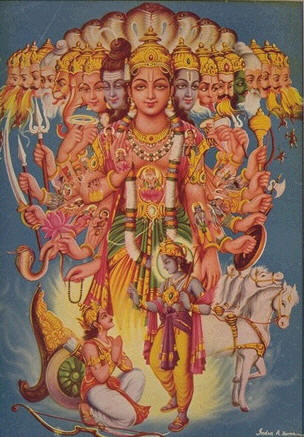

The three texts

for this class purport to represent the actual teaching of the

historical Buddha, who was roughly a contemporary of Socrates. In

some ways, they are in dialogue with the ideas we have seen in the

Bhagavad Gita; and in some important ways they are a critique of some of

those ideas. "Buddha" means literally "awake"; these teachings

explain how life looks when you are truly awake to the real.

What in these texts do you find challenging? What is utterly

unfamiliar to you? What are you comfortable with? How do

these texts differ from your own understanding? Why? What do

these texts want you to think? to do? How do they accomplish

this? What do they take for granted that you do not? What

difference does this make in your ability to grasp them? Who are

"you" in these texts? How should you act? Why? How are

the Buddha's answers similar to those we have seen? In what ways

is the Buddha critiquing earlier Indian ideas, such as we have already

seen? How are they different? What does suffering mean? How

does one find meaning in it? What is freedom? What is

important in life? In what ways is the Buddha's teaching a

critique of social norms? How does his teaching challenge your own

self-understanding? Why?

Before you come to class, write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal

with your first reflections on today's reading.

Read

before class:

|

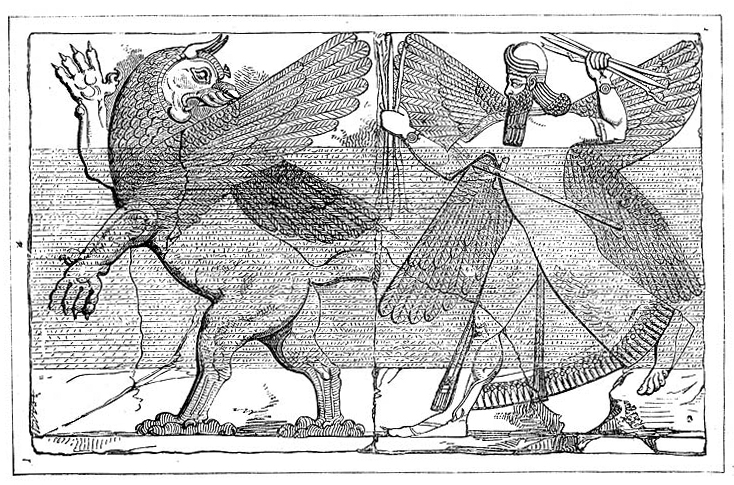

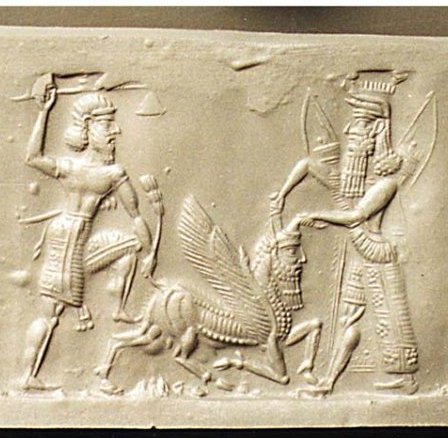

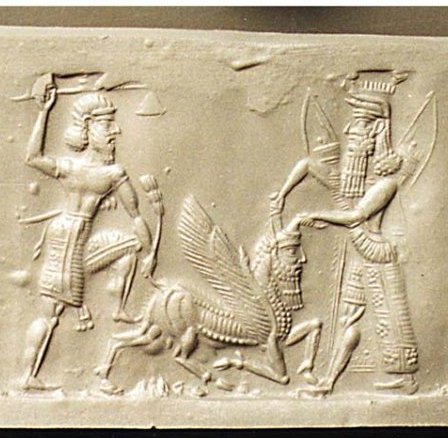

Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh is the protagonist of a number

of ancient Mesopotamian stories which appear to have been

widespread in the ancient Near East. What does the story

say about the difference between civilization and the wild?

What do you make of Gilgamesh's reaction to the death of Enkidu?

What do you make of the flood story?

Read

before class:

-

The Epic

of Gilgamesh (Myths from Mesopotamia, pp. 39-125

|

|

|

10/2 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

The Buddha and Buddhist teachings: The Heart Sutra

About the beginning

of the Common Era, the monastic form of Buddhist teaching was

challenged by an interpretation of the Buddha's teaching which

focused on the availability of the Buddha and his teaching to the

larger community, and not only to those who adopted the monastic

life. This "greater vehicle," the Mahayana, also developed the

ideal of the

bodhisattva, the enlightened being who postpones his own

entry into nirvana for the sake of the enlightenment of all sentient

beings. In this light, the Buddha is a permanent presence, and

enlightenment is a possibility for all who seek to uncover their own

buddha nature. It is, by and large, the Mahayana form of

Buddhism which moved into China, Korea and Japan. A further

expansion of the Mahayana, the Vajrayana, or "Diamond Way," became

the basic form of Buddhism in Tibet. The Mahayana text for

this class explores the subtler metaphysics and ethics of this

branch of Buddhist thinking.

The

Heart Sutra is a rather later Buddhist composition, dating from

somewhere in the early centuries of the Common Era, perhaps as early

as 100 C.E. Notice that in this text the Buddha is not the

speaker, but is a silent presence approving what is said. The

speaker is Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig in Tibetan), a disciple of the

Buddha who emerges in later Buddhist thought as the boddhisatva (the

person who perfectly realizes an ideal) of infinite compassion.

It is important in reading this text to note who the speaker is:

what is taught in this text is the foundation of compassion. |

Avalokiteshvara

16th Century Tibet

Rubin Museum of Art |

What do you find most compelling in this text? What is

most unfamiliar? How is it like other texts we have seen? How is

it different? What does the text take for granted? Note that the

text explains that all aspects of human knowing are "emptiness" (shunyata):

form, feeling, cognition, conception and consciousness are all equally

empty, and that their emptiness is not other than what they are. How

does that shape what it says? What does the text say about the meaning

of the universe? about the meaning of life? about you? How

does its understanding of the nature of reality shape its ethical teaching?

What does this text have to say about the meaning of the individual?

about how you should act? about why you should act?

What is freedom? How does one find meaning in suffering? How

does one find the transcendent in one's life? What is true human

community? How does compassion emerge as a consequence of this

teaching?

Before you come to class, write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal

with your first reflections on today's reading.

Read

before class:

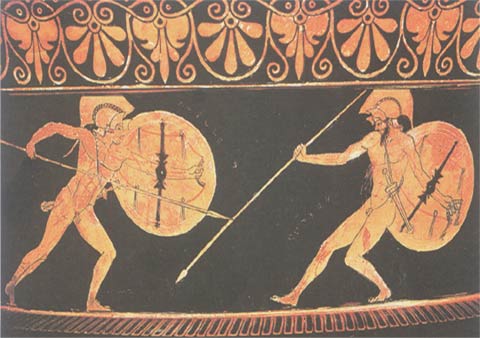

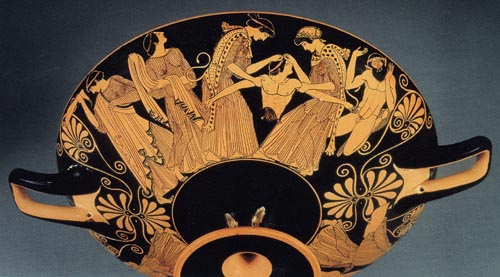

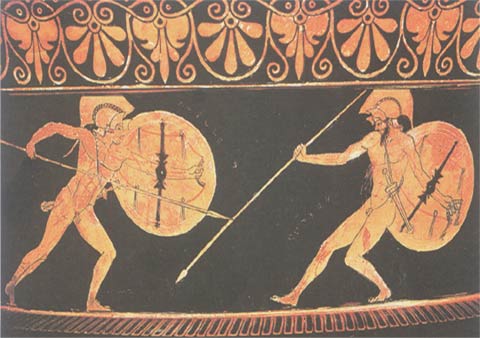

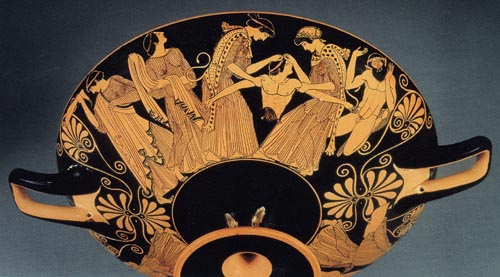

Achilles

fighting Hektor. Attic vase, c. 490 B.C.E. |

Ancient Heroes and Anti-heroes: The Iliad

Who is the hero? What is a hero? Is the hero an "I"?

In what sense is Achilles the hero of the Iliad? Is

Achilles responsible for his wrath? Why does the poem

begin with Achilles' wrath, but conclude with Hektor's funeral

rites? What in this poem made it the stories all Greeks

knew and remembered? Unlike most days, all sections will

meet together today for both morning classes to discuss this

material together.

Read before class: -

Heritage of World

Civilizations, pp. 86-101

-

The Essential

Iliad, Books 1-3, 6, 9, 14, 16, 18-24

|

|

|

10/21 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

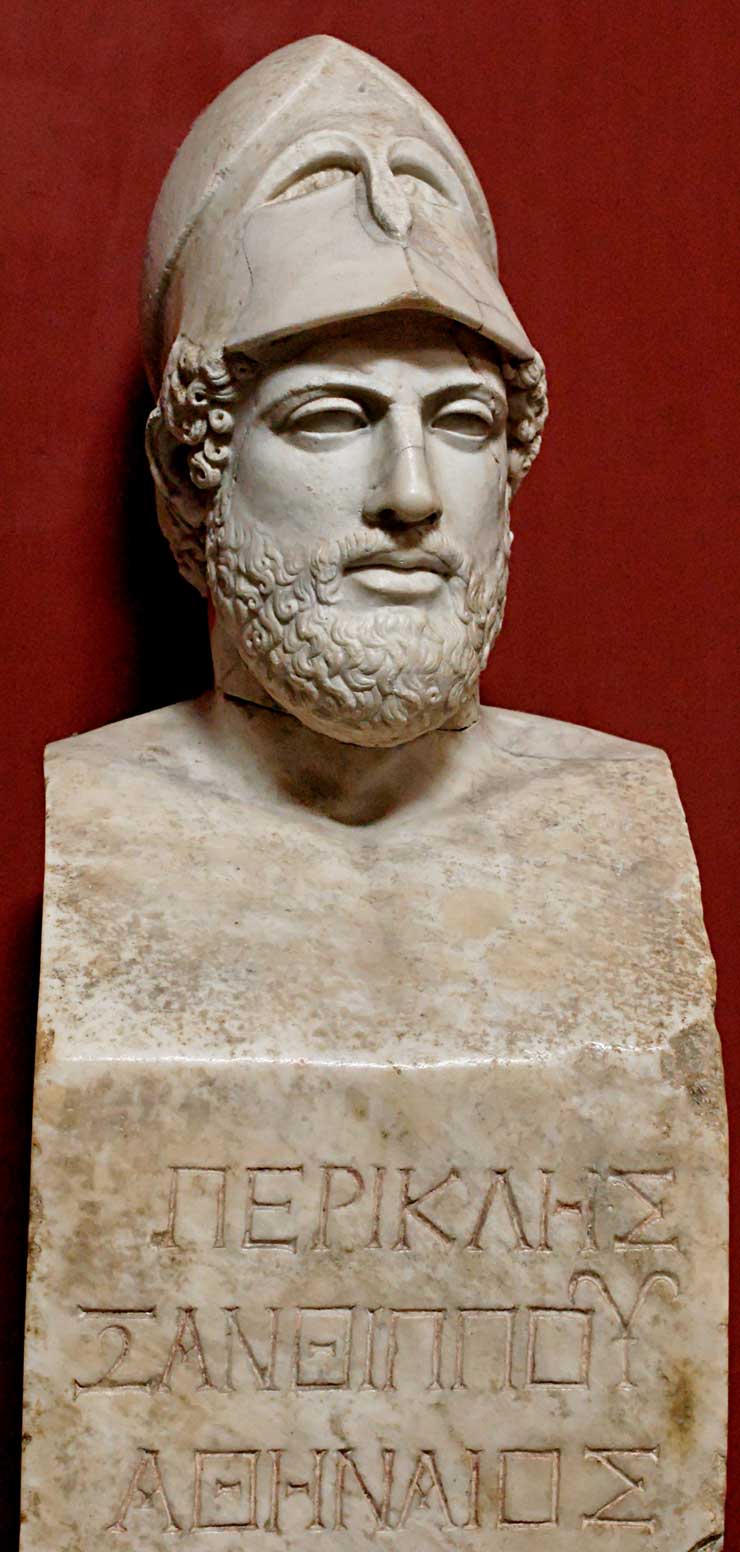

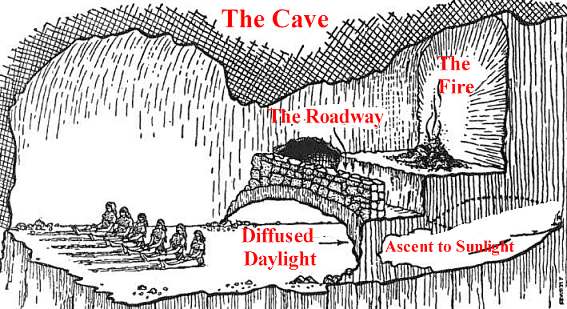

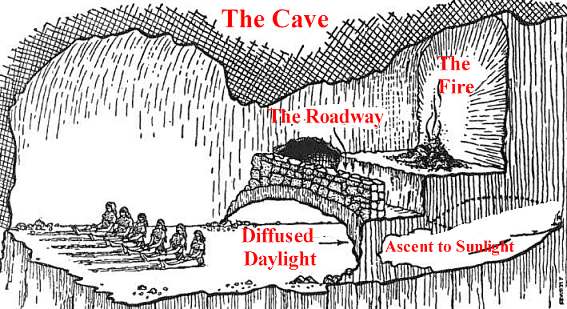

Plato's ”Allegory of the Cave” from The

Republic

Unlike the Apology, which was probably written

shortly after Socrates' death, The Republic is a much later

work, and the "Socrates" here may or may not accurately

represent the historical Socrates; he is certainly the

mouthpiece of Plato's own thought. The Republic is a

lengthy discussion of the nature of justice (clearly a sore

point for Plato, who was present at Socrates' trial); the

"Allegory of the Cave" is a discussion of the nature of the kind

of knowledge that will bring about a just society.

|

|

Do you recognize

the kind of thinking Plato is describing? Do you recognize the

"cave"? Do you live there? Do your friends?How do you

recognize what is real? How can you tell the real from the false?

How can you tell? What are you doing at university? How do

you connect your education with your future? Does that education

imply obligations to others? What might they be? What should

you do? Why? How?

Before you come to class, write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal

with your first reflections on today's reading.

Read

before class:

| The

Self and the Polis: Tragedy as katharsis

Aristotle says, in the Poetics,

that "Tragedy is, then, a representation of an action that is heroic

and complete and of a certain magnitude--by means of language

enriched with all kinds of ornament, each used separately in the

different parts of the play: it represents men in action and does

not use narrative, and through pity and fear it effects relief to

these and similar emotions"(1449b).

He uses the word "katharsis" (translated here as "relief") to

describe the ultimate effect of tragedy. What is the

"katharsis" (relief, purification, clarification) in

the plays of the Oresteia?

What kind of knowledge gives this "clarification"? How does

this way of knowing differ from "philosophical" knowing?

Read

before class: -

Aeschylus,

Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, The Eumenides

|

The Theater of

Ephesus |

By the end of this class,

we will have settled on the wording of the question(s) for the midterm exam. |

|

10/23 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

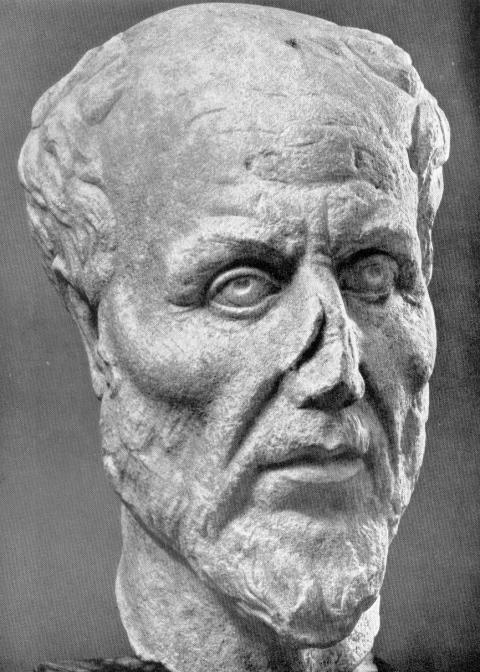

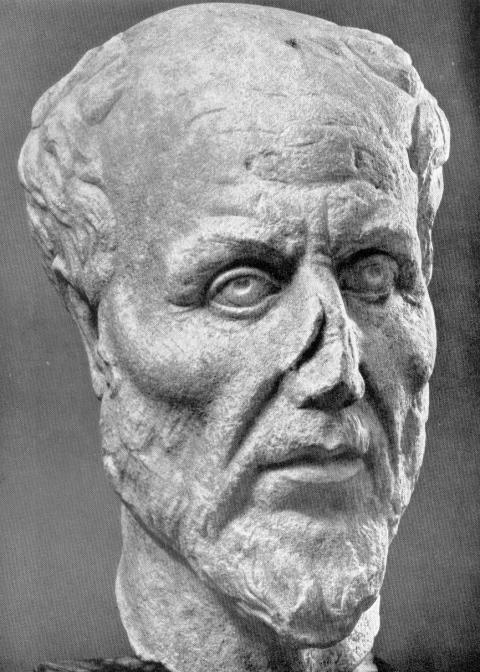

Plotinus:

Tractate on the Beautiful (Peri tou Kalou)

Plotinus synthesized the

fusion of Stoic and Platonic thought that was the preoccupation

of the Alexandrian philosophers of his time. His

development of the ideal of the Beautiful and the One in a

neoplatonic "monotheism" is both the culmination of ancient

Greco-Roman philosophy and the bridge to the philosophical

treatment of the idea of God which develops in Christian

thought. At the same time, he also appears to reflect the

influence of the Indian philosophers in the Alexandria of his

time; notice the echoes of Buddhist teaching in the Tractate,

particularly in the way in which he effectively denies intrinsic

(or absolute) existence to the things of our experience.

|

Is Plotinus consistent

with Plato in his understanding of knowledge?

How does Plotinus

argue to the existence of a transcendent Beauty?

Is that Beauty the

same as the Christian God?

What is the purpose of human existence in

a Plotinian world?

How does Plotinus' philosophical approach reflect

the social and political world of the third-century Empire?

Do you

recognize Plotinus' footprints in Christianity today? In Islam?

Read before

class:

- Reread

Socrates' speech in Plato's Symposium; in some ways, Plotinus is

giving a commentary on this text in the Sixth Tractate.

-

Click here for the annotated version of the

Tractate on the Beautiful

- For more

of Plotinus' work, you can follow this link:

Plotinus, First Ennead

(Scroll down to find the

sixth tractate; if that link does not go all the way to the sixth

tractate, click on the text-only link at the top of the page. That

version gives you the entire Ennead.)

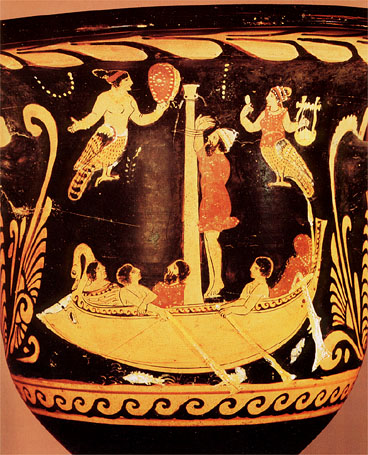

The Death of

Pentheus

Attic vase, c. 450 B.C.E. |

The

Self and the Polis: Tragedy as social katharsis

The Greeks found in their dramas a way of coming to understand a

number of conflicts that remained unresolved at the very core of

their civilization; the plays they continued to demand give us

insight into the nature of these conflicts. Indeed, some

of these conflicts can be seen in our own world; perhaps they

are inherent in human civilization. In any event,

audiences to this day continue to find understanding in these

plays. What is the "katharsis" (relief, purification,

clarification) in

Antigone, in Bacchae? What

conflicts do they dramatize, and how do they illuminate them?

What kind of knowledge gives this "clarification"? How

does this way of knowing differ from "philosophical" knowing?

Read before class:

- Sophocles,

Antigone

-

Euripides, Bacchae

-

Euripides,

Medea

|

|

|

10/28 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

Apollo, from

the west front of the Temple of Zeus, Olympia |

Greek Art and Architecture

Some of the most

enduring influences of the ancient Greeks that continue to

influence us are their extraordinary achievements in the visual

arts: their painting (mostly lost), sculpture and architecture.

No understanding of this period is complete without some

understanding of those accomplishments; we will spend some time

today studying them in preparation for our visit to the

Metropolitan Museum in a few weeks. It is important to

realize that these artistic accomplishments were not separate

from the rest of classical Greek culture: Socrates was a

stone-cutter by profession, and the Parthenon was commissioned

by Pericles.

Some

vocabulary which you may find helpful in speaking about this

art: geometric style, cult object, votive offering,

Kouros, Kore, drapery, sarcophagus, equilibrium, contrapposto,

relief sculpture, ideal type, realism, individual facial

figures, grave monument, Roman portrait bust, decorative wall

panel.

|

Midterm exam for HONS 1001

|

10/30

Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

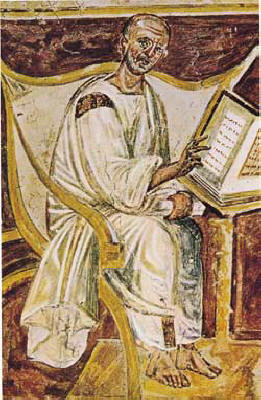

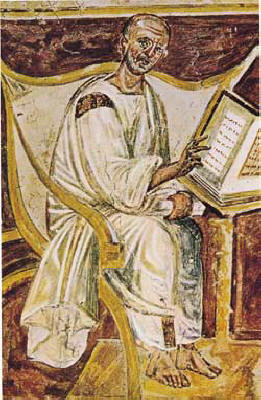

Augustine's

Confessions

The

Confessions is perhaps the first autobiography in Western

history, and it remains a classic of psychological

introspection. Augustine is a writer of unparalleled skill; pay

especially close attention to the beginning and the ending of

each book, for they summarize his thoughts.

How does

Augustine understand the meaning of human life? How does

he know this? Who is his partner in the dialogue in this

work? In what way is this familiar to you? In what

way is it different from texts we have seen before? What

difference does it make in your understanding of the text?

What do you take away from his description of his childhood?

Does it resonate with your experience? How? What are

the various meanings of "confession" as Augustine uses

this term to apply to this book?

Augustine

writes this book as a long, extended conversation with God: what

importance and meanings can be attached to this form; how would

it have been different without this dialogical character?

What kind of education did he receive, and what did he think of

it? |

"Take; read"

Benozzo

Gozzoli, 1465 |

Before you come to class, write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal

with your first reflections on today's reading.

Read

before class:

-

Augustine, Confessions,

Book 1

Midterm exam for CORE 1101 (hand in take-home exam) NOTE: This

assignment must be handed in no later than class on November 4!

Plato's

Republic

This class will be

devoted to examining questions raised in The Republic. The whole

class will meet together all morning for this discussion. Come

prepared to discuss the following:

-

How are we to take Socrates' suggestion that we shift the discussion

from the individual to the community (368e-369b)? Is it simply

a matter of seeing justice more clearly? What else is at stake

in this move?

-

Why is Plato so concerned with education (paideia) of the

young (literature and gymnastic)? And why does he want to

exercise such strict control over the poets? (How might

Euripides' and Aristophanes' plays have fared in Plato's new polis?

-

Correlate the great foundation myth (414d-415c) to the class

structure and the parts of the human soul. Does Plato get

these right? are any important things missing?

-

What finally does Plato claim that justice is and how does he arrive

at this definition? Do you see problems with his definition?

-

Socrates claims that three waves must be endured in order for this

new polis to come into existence: the equal education of men and

women, the new kinship structure and the philosopher ruler.

What are the main lines of each proposal, and how are these three

connected?

-

Plato's notion of the forms (ideas) plays the central role in the

education of the philosopher rulers with the highest form being that

of the good. What are the ways that Socrates attempts to

explain the form of the good (sun, divided line and cave)? Do

these make sense; do you see problems with any of these analogies?

-

Will the guardians be happy?

-

What problems does Plato have with democracy? Are his

criticisms cogent? Do you see any relationship of his

criticisms with problems today?

-

Why does Plato end his text with the story of Er? Do you see

any connection to the earlier story of the ring of Gyges? Does

the story of Er fit at the and? What purposes, if any, does it

serve?

Read before class:

-

Plato, Republic,

Books 7-10

|

|

10/31

Friday |

Trip to the

Metropolitan Museum of Art

We will spend Friday afternoon together on this trip to the Met.

The bus will leave from the Art Center by the main gate at 2:15 p.m.

As part of this experience, you will write a three-page description of

one of the myriad objects you encounter in this treasure house. We

will be assessing your ability to describe accurately and fully.

Begin your paper by identifying the object for someone who has not seen

it. Then give a detailed description of the object, including the

size, material, function of the object (if there is one), the time

period, the shape and ornamentation of the object. Then go beyond

the description of the image to a discussion of what it means.

Make a claim about the object

you are describing in relation to ideas or concepts you have learned

about the culture which produced it; formulate and argue a thesis about

it. The paper is to be handed in by November 18.

Some vocabulary which you may find helpful: geometric style, cult

object, votive offering, Kouros, Kore, drapery, sarcophagus,

equilibrium, contrapposto, relief sculpture, ideal type, realism,

individual facial figures, grave monument, Roman portrait bust,

decorative wall panel.

We will spend some time together in the Greek and Roman sections of the

Metropolitan. Afterwards there will be ample time for you to

explore other parts of the Museum; there's virtually no end to this vast

collection. Wear comfortable shoes!

Note that this is

Halloween!

You will be in New York City if you choose to take part in the

festivities after our visit to the Museum. You will be responsible

to get yourself home if you do. |

|

11/4 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

Augustine's Confessions

What

does Augustine mean by the "disintegrated self"? How is this

similar to, or different from, Plato's view of the self? the view

of the self in John? in the Gita? in Buddhist thought?

Why is he so troubled by the pear-stealing episode? Why is he

still brooding over it late in his life? What does he learn from

it? What do you make of it? How does his reflection on this

episode color his understanding of human action? What should you

do?

How does Augustine

interpret his boyhood prank in Bk. II and what significance does he

attach to it? For about ten years, he was associated with a

religious group called the Manichees; who are they, what do they believe

and of what importance is this to Augustine? As a young adult,

Augustine is perplexed by a number of philosophical issues: what are

they and how does he attempt to resolve them? Of what importance

are love and sex to him during these early years?

After class, write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal with

reflections on this week's reading and discussion.

Read

before class:

-

Augustine, Confessions,

Books 2 and 3

|

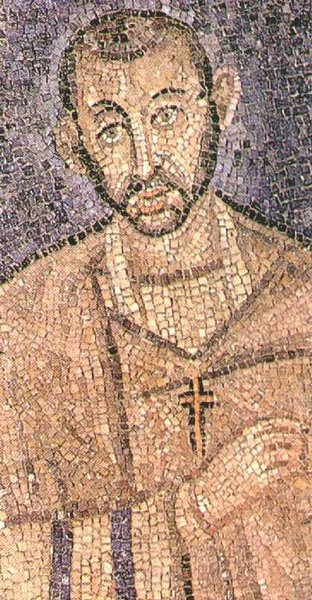

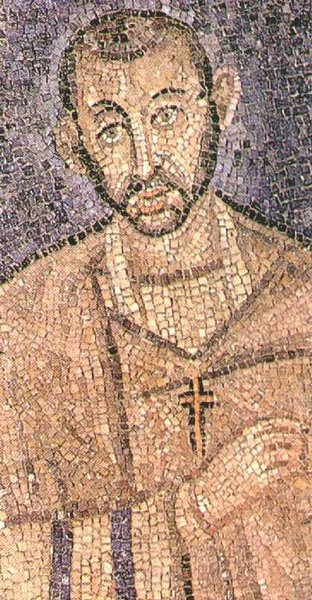

Augustine

Lateran Basilica, 6th century |

|

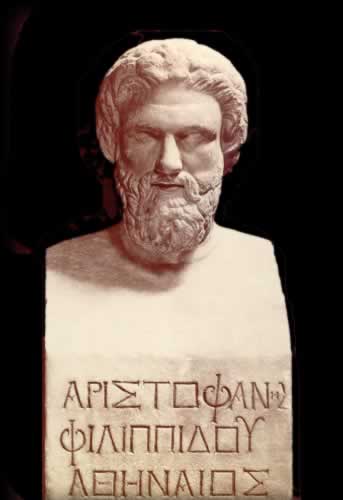

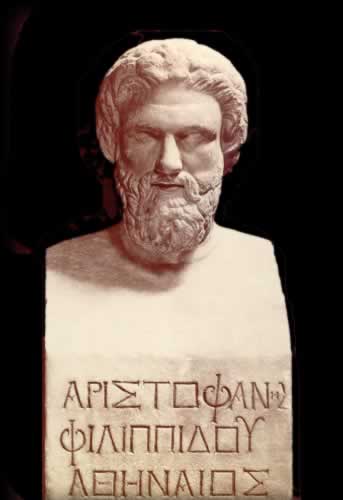

Athenian comedy

The

comic stage was another format in which the tensions in classical Greek

society became visible (and risible). It was not an accident that

a standard dramatic performance concluded with a comedy. Why are

these plays still hilarious? What do they tell us about our

society? What do they tell us about the Greeks? How does

Euripides' treatment of women differ from Aristophanes'? Why?

How are they similar?

Read

before class:

-

Aristophanes,

Lysistrata

-

Aristophanes,

The Clouds

Midterm

exam for the Journey course due at class today. |

|

|

11/6 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

Augustine's Confessions

How

does Augustine work his way through the question of evil? How does

this question go back to the pear tree episode? Do you find his

analysis of the question persuasive? Why? How? Does he

really answer the question he sets himself? Do you see his

alternatives still present in our world today? How does one find the

transcendent? How does one imagine it? What does it mean to

suffer?

Why does he go to Rome

and then to Milan? What ambitions does he have" What is

happening in the western Roman Empire at this point? What influence

does Ambrose have on him? Book VII describes Augustine's

"intellectual" conversion; pay attention to the importance of

"platonist" philosophy and how he sees this in relation to Christian

revelation. What are the main features of this aspect of his

conversion? How does Plotinus shape Augustine's answers?

Before you come to class, write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal

with your first reflections on today's reading.

Read

before class:

-

Augustine, Confessions, Books

7-8

Image: Ambrose of Milan, 5th

century mosaic, probably a portrait, Sant'Ambrogio, Milan |

|

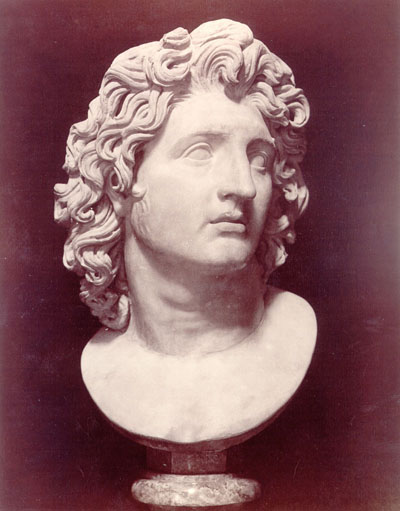

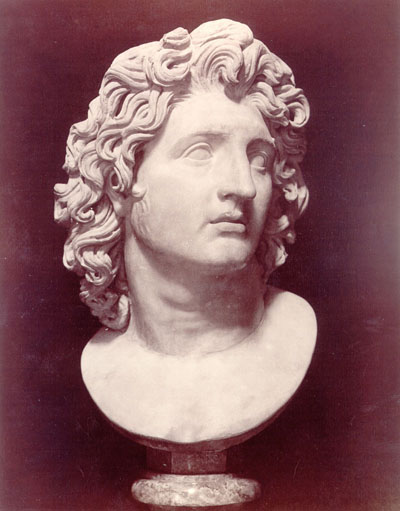

Alexander |

Aristotle,

Alexander and Hellenism

With Alexander's unification of the eastern Mediterranean and

western Asia into a single cosmopolitan entity, the thought

forms of classical Greek thought became the common language of a

wide variety of human societies. The resulting synthesis

of Greek, Egyptian and Middle Eastern thought became the basis

both of Roman imperial civilization and of the Christian church.

We are still the heirs of Alexander.

Read before

class: -

Heritage of World Civilizations, pp. 118-129

-

Aristotle:

Physics,

Book II, parts 1-3

-

Aristotle, On the Heavens,

Book I, parts 1 - 4;

and

Book II, parts 13-14

-

Aristotle,

Metaphysics,

Book 12, parts 7-9

|

|

|

11/11 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

Augustine's Confessions

What

do you make of Augustine's final conversion? What made it difficult?

What made it possible? How did his intellectual struggles pave the way

for it? How does one come to a vision of life? How does one

understand the meaning of beauty? of truth? How does your own

spiritual journey reflect Augustine's? How does one construct

community?

Book VIII culminates in

Augustine's moral conversion: what are its main features; with what

(in himself) is he struggling; how does his conversion finally come about?

What is the "vision of Ostia" as Augustine recounts it in Book IX?

Throughout the book, what does Augustine consider the problem to be?

How does he conclude it can be dealt with?

|

The baptistery

under the Duomo of Milan, where Augustine was baptized. |

After

class, write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal with your reflections

on what you've learned from discussing Augustine's Confessions.

Read before class:

-

Augustine, Confessions, Books

9-10

|

|

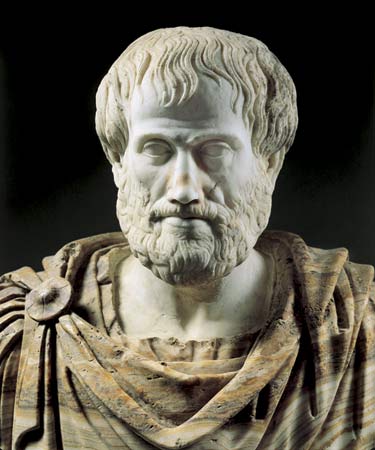

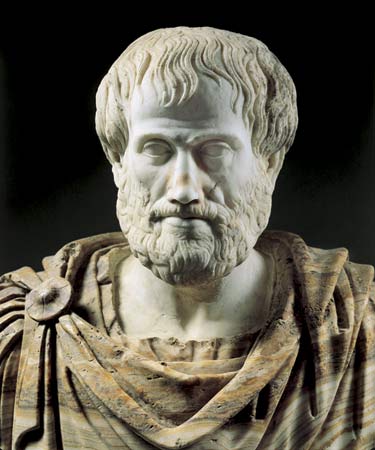

Aristotle

Read before

class:

Aristotle, marble portrait bust, Roman

copy (2nd century BC) of a Greek original (c. 325

BC); in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome |

|

|

11/13 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

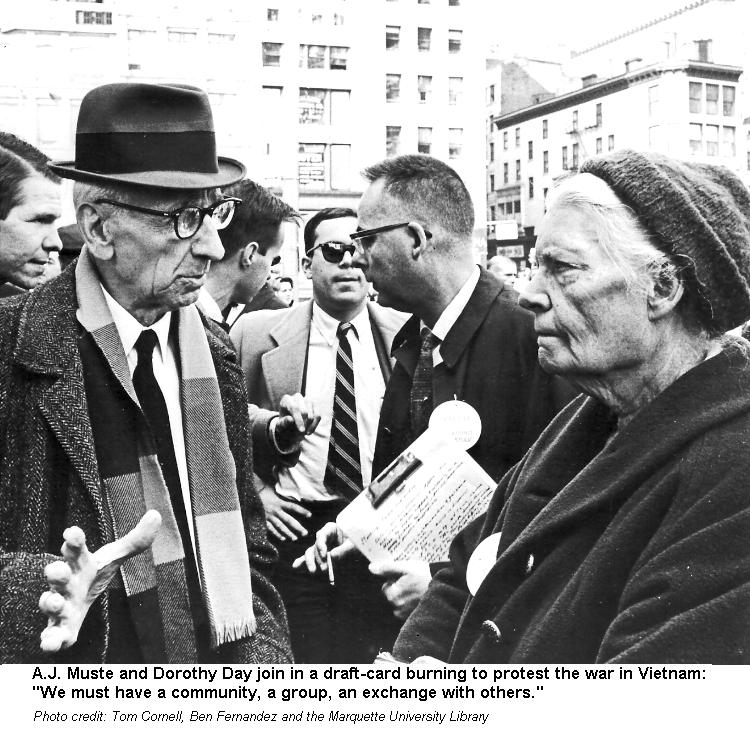

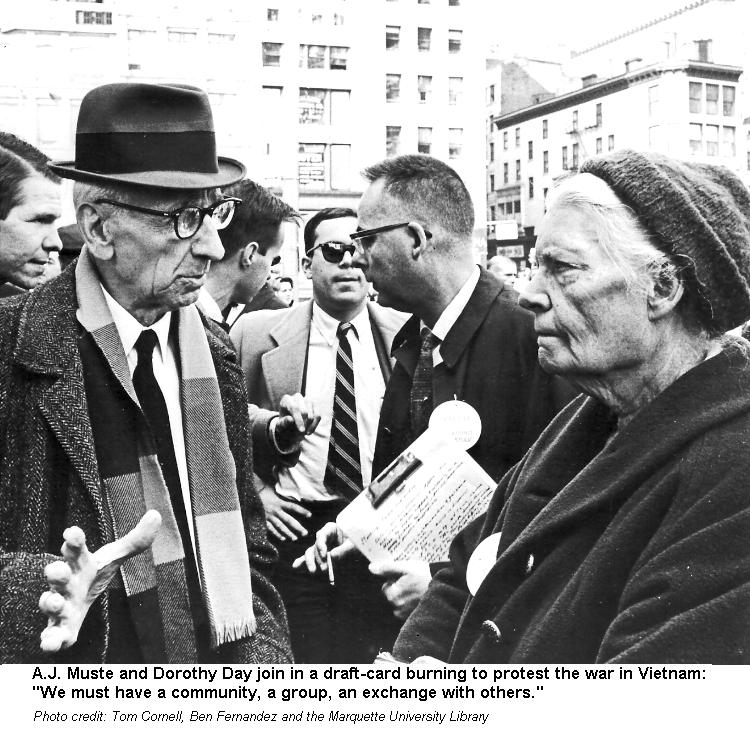

Dorothy Day's The Long Loneliness

Dorothy Day

(1895-1980) was the founder of the Catholic Worker movement.

Raised in the Episcopal Church, she was a Marxist activist during

the First World War and then became a Catholic after the birth of

her daughter in 1927. Together with Peter Maurin she began to

publish The Catholic Worker in 1933, and opened the first

Catholic Worker house in the fall of that year. The Catholic

Worker movement from that time forward became a leading voice for

service to the poor, for pacifism, civil rights, for the rights of

farm workers, and against anti-Semitism and war, whether the

Spanish Civil War, World War II, the Cold War, the Korean War, and

the Vietnam War. Among her many admirers was Mother Theresa of

Calcutta.

Some questions to

think about as you read:

|

Dorothy Day |

-

How does Day describe her

religious sensibilities that she had as a child?

-

What were her relationships with family members and how did these affect

her life (father, mother, and especially her baby brother)?

-

What were her experiences as a student and her time at college?

-

What social issues does Day become aware of during her time at college

and immediately afterward and how is she moved by them? What does she

think she should do and why? How are these concerns related to her

journalism work?

-

What are the effects of her participating in a being jailed for the

protests in Washington, D.C. in 1917?

-

Why was she attracted to Marxism and Socialism as a young woman? What

answers do these systems provide for her? What questions does she have

about these ideologies?

-

Her family life is very important to her during her time on Staten

Island; how does she describe her relationship to her partner and the

birth of her daughter? Why did she and Forster end their relationship?

At what point is her spiritual journey and how does she understand it?

-

Who was Peter Maurin and what influences did he come to have in her

life?

-

Identify the core beliefs of the Catholic Worker and how did these come

to be discovered and lived out? How do Day and Maurin see their

relationship to the Catholic Church?

-

Why a newspaper?

-

What's love got to do with it? How is love understood and practiced by

Day, Maurin, and the others who create the Catholic Worker?

Read before

class:

- Dorothy

Day, The Long Loneliness, Introduction by Robert Coles,

and pp. 15-83; 93-109

|

Hellenistic and Roman Philosophical Thought

With Alexander's unification of the eastern Mediterranean and

western Asia into a single cosmopolitan entity, the thought forms of

classical Greek thought became the common language of a wide variety

of human societies. The resulting synthesis of Greek, Egyptian

and Middle Eastern thought became the basis both of Roman imperial

civilization and of the Christian church. We are still the

heirs of Alexander.

Read before class:

Recommended reading:

Image: Torso of a

boddhisattva, Gandhara, Pakistan, 1st-2nd century C.E. The

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Note the Greek influence on the form of

the body, showing the degree to which western and southern Asia were part of

a world stretching to Spain and Britain.

|

|

|

11/18 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

Dorothy Day

Continued discussion of

issues raised in The Long Loneliness. Reflect more on the

questions raised earlier about her journey.

Read before class:

- Dorothy Day,

The Long Loneliness, pp. 113-138

Image: Ade

Bethune, Dorothy Day, Dorothy Weston, Jacques Maritain, Peter Maurin

at the Catholic Worker house, 1934 |

|

|

The Roman Republic

Livy on the Roman

concept of female virtue, Polybius on the constitution of the

Republic.

Read before class:

Deadline for handing in your paper on an object from the Metropolitan

Museum.

The

Curia Iulia, seat of the Roman Senate, in the Roman Forum |

|

|

11/20 |

|

Dorothy Day

Continued discussion of

issues raised in The Long Loneliness. Refer again to the

questions raised above concerning the issues her book raises.

Read before class:

- Dorothy Day,

The Long Loneliness, pp. 169-235; 263-286

|

|

Julius Caesar |

Julius Caesar and the fall of the Roman Republic

Julius Caesar was one

in a series of warlords whose private armies continually threatened

the stability of the Roman Republic, which was itself collapsing

under the weight of administering what had suddenly become a great

world empire with institutions developed to rule a modest-size city.

Read

before class:

|

Fourth essay topic

: (due December 2) |

|

11/25

Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

|

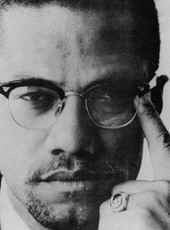

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

Malcolm X's

Autobiography recounts his transformative journey into the

leader he became. He raises questions of the meaning of the

American experience that continue to challenge us. How does

one find meaning in oppression? in suffering? What makes

for a truly human community? How does one's vision of the

transcendent affect the kind of community one builds? How do

our cultural values get in the way of genuine community? How

do we get past the cultural presuppositions that prevent the

formation of genuine human community? As you read, think about

the power of people's attitudes on Malcolm's personal growth and

development. What kind of person did he become as a

consequence of those attitudes, his own and others'?

Before

you come to class, write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal

with your first reflections on today's reading. |

Malcolm X |

Read before class:

Augustus Caesar,

Vatican Museums |

Rome as Republic and as Empire: Vergil and the Aeneid

Vergil's Aeneas is both an epic hero on the model of Achilles

and Odysseus, and a type of the model Roman, invented to justify

the new imperial despotism of Augustus Caesar. The

tensions between Vergil's epic aspirations and the political

nature of his commission made his work an enduring classic.

Vergil's other poetry also articulates an idealized version of

what it meant to be "Roman." Maecenas, addressed in the

first verses of the Georgics, was an immensely wealthy adviser

to Augustus and patron of several of the poets of Augustus'

court, including Vergil and Horace.

Be prepared to discuss:

1. The driving force of the

Aeneid: a divine plan?

2. The intervention of the gods,

especially in Books 1 and 7.

Read before

class:

-

Heritage of World Civilizations, pp. 202-220

-

The Essential Aeneid, Books 1, 2, 4

|

|

|

11/27 |

|

|

12/2 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark

|

|

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

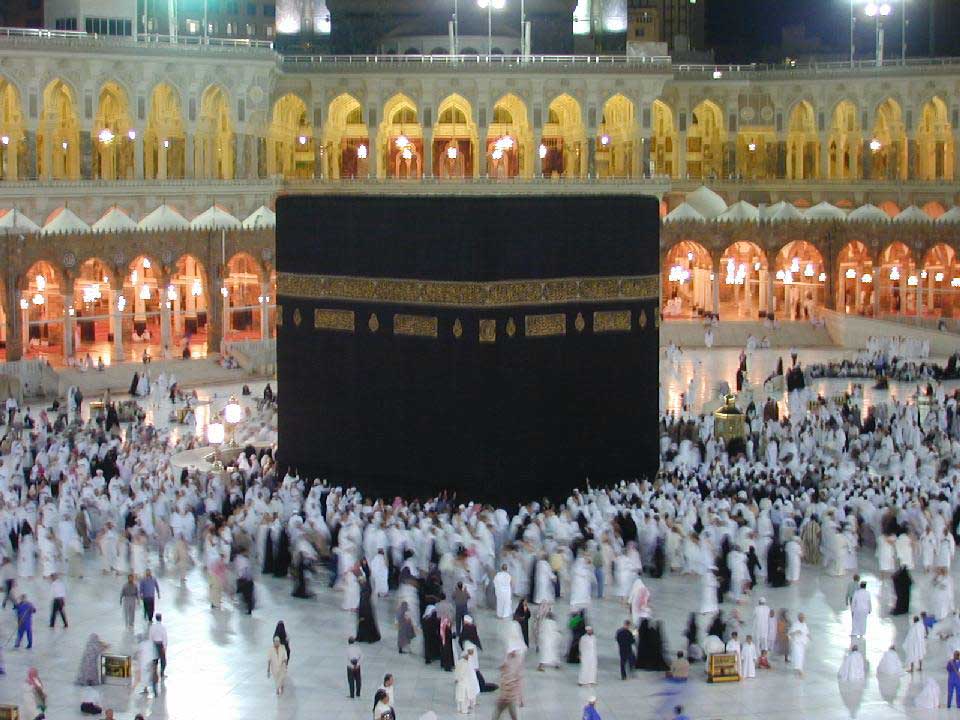

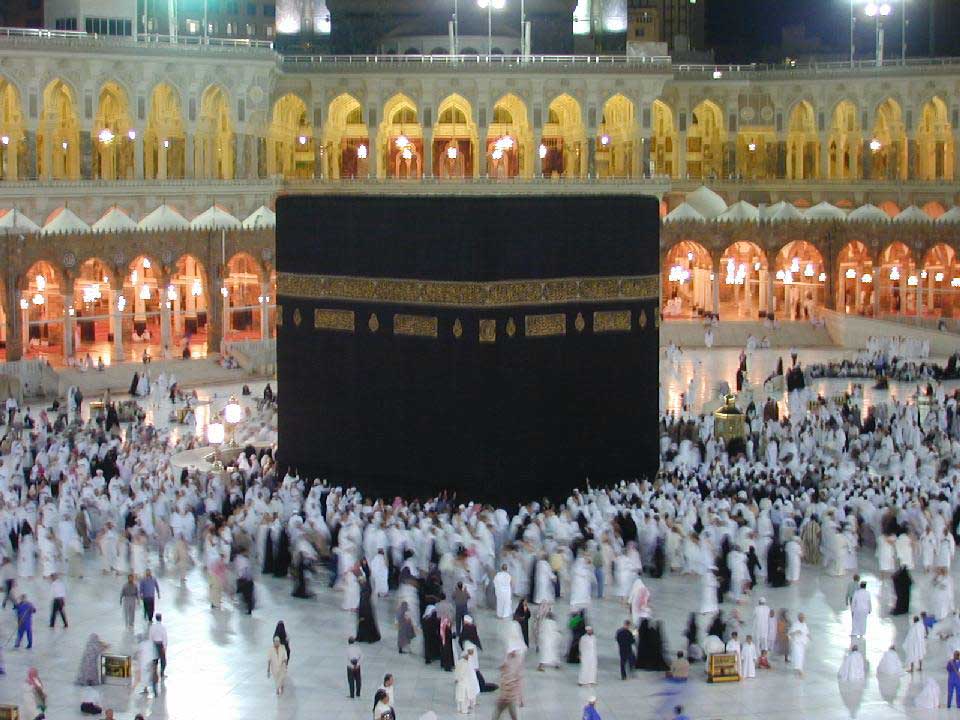

Malcolm X also raises the question of structural oppression. Is it

enough to be a good person as an individual? Do our responsibilities

go beyond personal goodness? Is it enough to pursue personal

happiness? How can we appreciate the humanness of others who are

different from us? How can we find common ground with them? What

makes this appreciation difficult? How? How does Malcolm X find

a grounding for this appreciation in Muslim values? How do those

values appear to you? How did his experience at Mecca change him?

Image: The Kaaba

|

|

After

class, write a few paragraphs in your My Blog/Journal with reflections on

this week's reading and discussion.

Read

before class:

-

Malcolm X, The Autobiography of

Malcolm X, chapters 16, 17, 18.

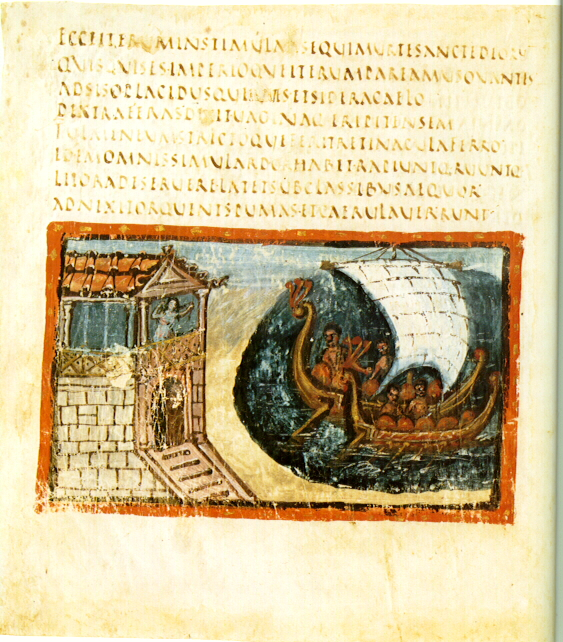

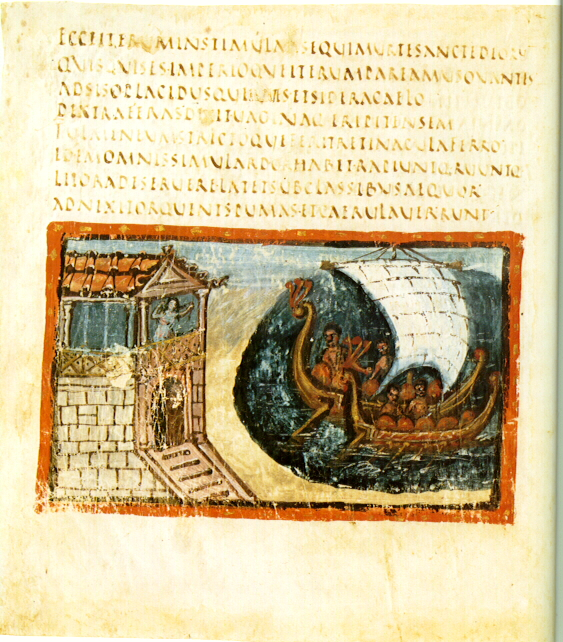

Folio 40r of the Vatican Vergil: Dido sees Aeneas sail away.

The Vatican Vergil is a codex of the works of Vergil written c. 400

C.E. |

The Aeneid

and other poetry of Vergil and his contemporaries

The Odes of Horace are

another perennial monument of the Augustan project.

Published in 23 B.C.E., they give a rounded picture of the Rome

that was settling in to rule the world. The first six Odes

of Book III, the "Roman Odes," portray the social, moral,

political and religious aims of the new Roman Empire as Augustus

would have them accepted. What does it now mean to be a

"Roman"?

Read before class:

-

The

Essential Aeneid, Books 6, 7, 8, 12

-

Horace,

Odes (in Blackboard)

|

Aeneas and Anchises |

Fourth essay due. |

|

12/4 Ahr/Conway

Booth/Stark |

Course Summary

|

The Stoics

The first century CE brought a renewed interest in philosophy, but

with a decidedly different approach. Rather than pondering

ideal forms, or causes, the "moral" or "practical" philosophers were

concerned with the question, "How should I live?" How do the Cynics

answer this question? How do the Stoics? the Epicureans?

Do you recognize some of these answers in the world we live in? Who

are the Epictetuses of our contemporary culture?

Read before class:

Marcus Aurelius,

Capitoline Museum, Rome |

Come to class prepared to

formulate the list of topics, persons, ideas and things for the final

examination. We will formulate the questions for the exam in the next

class. |

|

12/9 |

Course Summary

This course was designed to

enable discussion of core texts dealing with issues from the Catholic

intellectual tradition, with special attention to how they can inform our

journeys of transformation. Faculty prepared material for you to study,

discuss together, and think about individually. In a brief essay, reflect on

your course activities -- reading, writing, listening, talking, thinking,

and other in-class and out-of-class experiences -- the totality of your

course work. As you reflect describe the mileposts and potholes of

your own journey along this course of study. Hand in an essay of about

five pages dealing with the following questions, by noon on Tuesday December

18, or earlier by email. This essay will constitute 20% of your final

grade.

Your task is to write a

unified narrative reflection, examining what you have learned through this

course.

The work is divided into two stages. You should submit the pre-writing as

well as the finished essay.

Stage 1, pre-writing. The questions below have been posed to help guide your

thinking, as you consider the past semester in the Journey of Transformation

course. Begin working on your essay by answering these questions in as much

detail as possible. Certainly your answers should include quotations from

the class material, such as texts, visuals, discussions, or service

experiences, as well as your own analysis and conclusions.

What new knowledge have you gained, and by what means have you learned it?

What understandings do you have that are clearer and/or fuzzier now than

before, and how did this came about?

Have any of your attitudes changed, and in what ways? How did this happen?

Have you learned new ways of thinking about what you know? How did you learn

these ways of thinking?

Have any of your personal goals changed, and if so, what led to the change?

Stage 2, writing the essay.

Based upon your answers to the questions, reflect upon your experiences as a

whole, over the past semester, and decide how these separate parts are

related, so you can write an essay with a unified theme and an organized

structure. You might choose a chronological narrative, describing and

interpreting your experiences as they happened one after the other. Or you

might choose to describe pivotal events or insights in the order of their

importance to you. Or you might structure your narrative as a dialogue with

one or more of the authors that we read, quoting them, and relating the

quotations to your own thoughts. Or you might pose a paradox and write about

its resolution. Or you might come up with another organizing theme of your

own.

|

Review for final exam

We will formulate the

questions for the final examination in this class, as well as tie

together sundry other loose ends. The examination will, of

course, be cumulative.

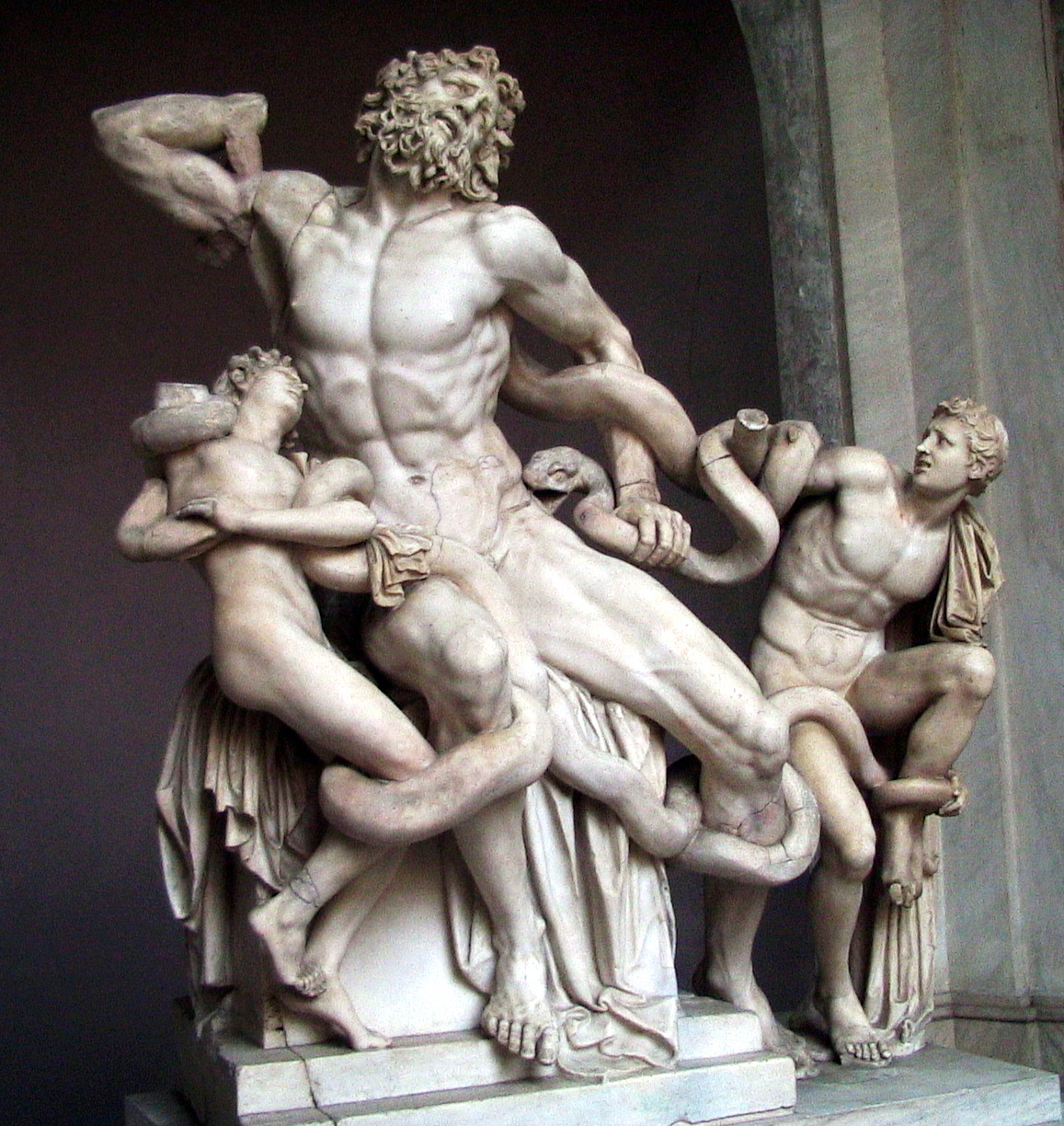

Image: The Labors

of Hercules. 3rd century Roman mosaic, Madrid Archeological

Museum |

|

|

|

12/12 (Friday) |

|

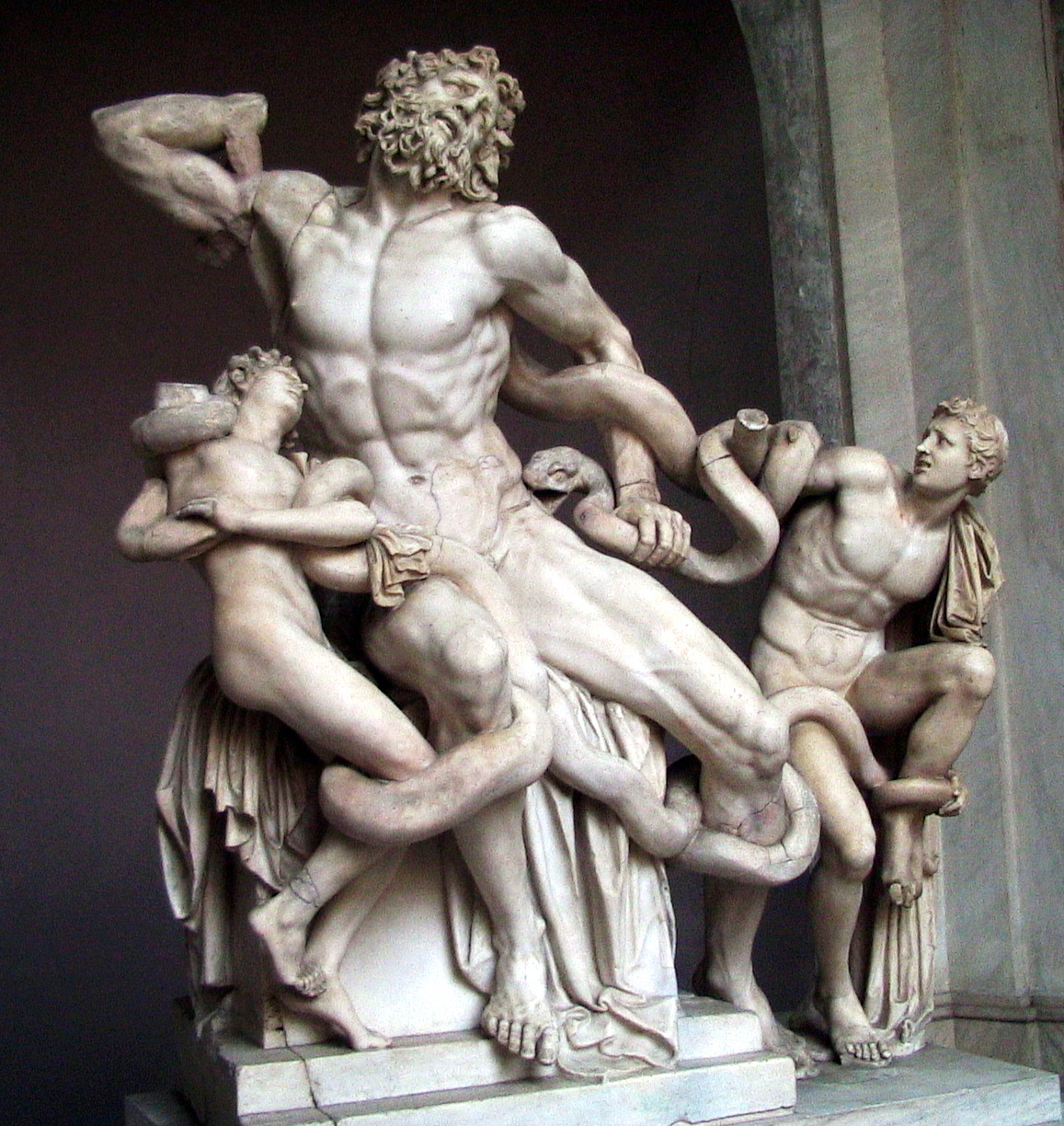

Laocoon |

Final Exam 12:45 p.m.

|

|